- Home

- Roxanna Elden

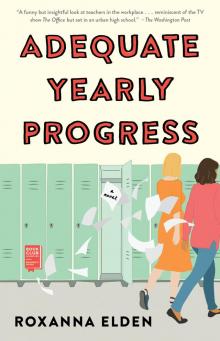

Adequate Yearly Progress Page 6

Adequate Yearly Progress Read online

Page 6

“Well, you chose the wrong career,” said Regina. “Ain’t no men in teaching.”

“Hey!” Hernan placed both hands over his heart as if he were deeply offended.

“You know what I mean, Hernan. Okay: there are a few men in the teaching profession. But Hernan is the only good one.”

“Better,” said Hernan. “Much better.”

Candace smiled at him.

“That reminds me,” said Lena, “if you all are into the spoken-word scene, there’s this poet, Nex Level, who’s gonna be performing at Club Seven next Friday.”

“Sorry, Roland and I are taking a weekend cruise.” Breyonna signed her credit-card slip.

“Anyone else?” asked Lena, looking toward Regina and Candace as Breyonna said her goodbyes and headed out.

Kaytee took advantage of the distraction and slipped the exit tickets from her bag.

“Ain’t no men at poetry clubs,” said Regina. “Those things are always ninety percent women.”

“I’ll go,” said Hernan.

A chorus of Oohh, Hernans rose from Regina and Candace.

“Cool,” said Lena. “Um… I’ll give you the details at school?”

It was now or never. Kaytee took a deep breath, then pushed her plate aside, placing the exit tickets on the table. She felt eyes on her as she began writing, but she did not allow herself to look up. She had just finished grading the third ticket when she felt a kick under the table.

“Girl, what are you doing?” whispered Lena.

“Just grading some papers.” Kaytee tried to sound nonchalant, as if such student-focused multitasking were a natural extension of happy-hour fun. “I need to get some feedback to my students soon so they—”

“Put them away!” Lena hissed. “You’re killing everyone’s buzz.”

THE MYSTERY HISTORY TEACHER

www.teachcorps.blogs.com/mystery-history-teacher

“Quit Taking It Personally”?

I was told today, in a whole bunch of different ways, that I should quit taking my students’ failure so personally. There’s an attitude toward our marginalized students of color that seems to come from every other teacher at my school. I won’t go into detail.

But then she deleted the last sentence, because perhaps she would go into detail. She was still hungry after eating only celery sticks at happy hour, and she’d stopped grading papers after Lena kicked her under the table. This meant the exit tickets still loomed over her weekend.

But it was more than that. She’d expected the teachers at happy hour, of all people, to care as much about low-income students’ success as she did. Instead, they’d sounded just as bad as Patty Towner. Kaytee wondered, suddenly, if she was the only teacher at her school who took it personally.

And then she began typing again.

She changed what she had to in order to keep the story anonymous but left the main ideas intact: How, even at a table full of her colleagues, she’d felt like the only advocate for her students. How she’d had to remind her own mentor teacher that the kids were not hopeless. How the teacher next door, maybe the worst offender of all, taught lessons about democracy but ran her classroom like a dictatorship. By the time Kaytee reached the last paragraph, she’d nearly forgotten how hungry she was.

Today I tried to lead by example and show my colleagues that when it comes to breaking down barriers for students, there’s no such thing as time off—even if that means grading papers during happy hour. Maybe I’m the only one, but I’ll say it: my students’ futures matter to me. And I am not going to quit taking it personally.

COMMENTS

Yellow Brick Road University Teachers! Get an online masters degree at www.yellowbrickroaduniversityonline.com.

NaughtyTeacherDetentionXXX Have you been a bad boy? Cum see me after class! Check out my naughty detention pics and so much more. www.naughtyteacherseemeafterclass69.com

Click here to write an additional comment on this post

MAKING HEALTHY CHOICES

“O’NEAL RIGBY! WHAT are those girls doing up there in the stands?”

“Yelling my n—” O’Neal began, then stopped, his smile disappearing. This was the wrong answer.

“Yelling. Your. Name.” Coach Ray spoke slowly, using what he’d heard players call his calm before the storm voice. “Why? Because they like football so much?”

O’Neal Rigby stared at his cleats. He knew what was coming. “No, Coach.”

“Do girls like football, O’Neal?” Coach Ray used Rigby’s first name on purpose—Rigby was what crowds screamed when things were going well.

And things were not going well.

“No, Coach.”

O’Neal Rigby was the star of the Killer Armadillos. Usually, he was everything a coach could ask for. But he lost focus when girls were around, clowning and doing these stupid little dances when he caught the ball and then, almost immediately afterward, making some idiot mistake. With the first game of the season coming up, the Killer Armadillos had no time for mistakes. Plus, after what had happened last year, the whole keeping-your-dick-in-your-pants thing could not be reinforced too much.

“What do girls like, O’Neal?” He was leaning in now, staring right into the face mask of Rigby’s helmet.

“Attention. Coach.”

“And…?” All the other players were gathered around now, listening. Every one of them knew the rest of the sentence, and fuck if O’Neal Rigby was going to get back on the field without finishing it.

“Football equals attention.”

Coach Ray could have kept going if he wanted to. If he really wanted to drive the point home, this was when he’d ask the player whether he was a boy who liked football or a girl who liked attention, in which case he might want to go ask Ms. Watson if she had a cheerleading uniform in his size.

But he saved those moments for when he really needed them.

Right now, that didn’t seem to be the case. O’Neal Rigby, despite being three inches taller than his coach, looked as sorry as a child. Which was part of the whole thing: In a way that a kid who’d just turned eighteen could never understand, he still was a child. But a child who was six foot five, over 250 lbs, and already getting attention from the local media could easily be convinced that he was an adult. As a result, the moment a top player was about to cross into the bright end zone of opportunity was also the moment he was most likely to pull some knuckleheaded fucking fumble that cost him a free ride to college and sometimes even got him a criminal record on top of that, not to mention getting the school’s name in the paper and leaving the coach hanging on to his job by a thread. Fucking Gerard Brown.

But Gerard Brown was not the topic right now.

The topic was Booker T. Washington High School, who the Armadillos would be playing in their first game and who were known for coming into the season ready. No way Booker T. was going to lose because of some girl.

Coach Ray addressed the whole group now. “The first game sets the tone for the year. So why don’t y’all tell me right now—how’s this season supposed to end?”

“Championship!”

“And how’s this season gonna end?”

“Championship!”

“You think you’re just gonna show up on the day of the fucking game and decide you want to win?”

“No, Coach!”

“Remember, your game face is not just for the game. And it’s not just for your face. Everything y’all do between now and that first game is gonna decide whether we win. So get those inner game faces on and go play. Let’s go! ”

That inner game face. That was what he always came back to. That was what you needed to do football right. On the field, you didn’t think about last year, or the heat, or the fact your truck needed fixing, or that God, who had to know men communicated anything worth knowing through sports, had seen fit to send you two daughters whom you now had to support with almost half of each paycheck. Keeping an inner game face meant blocking out any thoughts that didn’t fit your

current objective.

Here was the current objective: to get ready for the first game of the season. And to remind this year’s star team member that he was more team member than star.

And so Coach Ray was thinking of nothing else as he caught O’Neal Rigby by the arm, just before they went back out onto the field, and said, “Learn from other people’s mistakes, son, or your mistakes are gonna be the ones people learn from.”

Like mine, he didn’t think. Didn’t think about it at all.

FUNCTIONAL ORGANIZATION OF DATA

THREE-RING BINDERS WERE the highest level of the organizational hierarchy, according to Maybelline. They were not like flimsy manila folders, which one could fill with leftover worksheets, then stash in some accordion folder inside a file drawer. They were not like pocket folders, which one could stuff with meeting notes and forget in a pile. Binders required full attention. One had to neatly label each divider before anything could go into them at all.

And so, with this year’s district-mandated data binder in front of her, Maybelline couldn’t possibly have time to notice the whistles and yells on the football field outside her window. These were not important. What was important was the first set of pre-test results, which Maybelline had printed days ago. She’d organized the results by class, as required, and when that didn’t seem quite sufficient she’d created additional spreadsheets based on each of the new curriculum standards. Then she’d color-coded students’ names based on how they’d done on each standard. Ever since, she’d been checking her e-mail for the arrival of the final element: the official cover sheet on which she would input her average pre-test scores and projected goals for the TCUP. It hadn’t arrived until this morning. But still, she would have her data binder set up a full week before the due date, probably before any other teacher in the school.

Out in the hallway beyond her door, she heard sounds of teachers leaving for the day. These were the same teachers, Maybelline was sure, who would have to rush to finish their binders by the deadline. Most of her colleagues fell behind on paperwork. They forgot to print out pre-test results. They misplaced forms.

As the year went on, they waited too long to grade papers. Then, before they knew it, they were accepting stacks of makeup work from students—the ultimate sign of a weak organizational system. Maybelline Galang never accepted makeup work.

She sliced open a fresh box of plastic sheet protectors. What better way to show that one had not waited until the last minute than to encase each page in its own glossy sheet protector? The time would come to provide documentation. And when it did, Maybelline would be ready.

It would be a different story for some of her colleagues. Lena Wright, for example, probably had her pre-test printouts in some overflowing manila folder belching its contents onto a shelf. One look at Lena’s paperwork would be enough to show any observer she was more concerned with organizing happy hours than with organizing data.

Maybelline slipped the final, completed form into its sheet protector with what should have been a victorious swish. So why did something about it feel empty?

Maybe it was because, even with the deadline only a week away, Dr. Barrios had waited until this morning to send out the goal-setting cover sheet. This suggested that, once again this year, he wouldn’t be coming around to check the binders, which meant, once again, he would not know who’d finished on time. Maybe he didn’t even care if everyone procrastinated on their data binders, just as they did on everything else.

Everything except football. That they took seriously.

The racket from the field seemed to be directly below her window now, the pounding of players’ cleats trampling her own sense of accomplishment. Suddenly, she was consumed with the need to show Dr. Barrios that, even though he’d sent out the cover sheet way too late, she had finished early.

She headed to the office to sign out for the day, taking the binder with her.

The principal greeted her with a wide smile. “Ms. Galang! You’re here pretty late!” He always said this when she stopped by his office after school hours.

“I’m always here until this time. Sometimes even later.” That was another thing that bothered her: How could he not notice which teachers stayed late? If she were running a school, she’d keep an eye on the staff parking lot, noting the order in which teachers went home. “Actually, I just finished my data binder, even though we didn’t receive the goal-setting sheet until this morning, and I thought you might want to see…” She opened the binder, its sheet protectors glowing like treasure under the office lights.

“That looks great, Ms. Galang!” Dr. Barrios’s hand inched toward his desk phone. “Listen, I have a call scheduled right now, but Mr. Scamphers handles most of the evaluation stuff. I’m sure he can help you.”

“I don’t need help,” clarified Maybelline. “I finished already.”

“Okay, great. Take it over to Scamphers. He’s a genius at this stuff!”

Dr. Barrios put the receiver to his ear, squinting at a paper on his desk as if it required careful attention.

Maybelline’s frustration grew. She didn’t need Mr. Scamphers to be “a genius at this stuff.” She had finished early.

Even as she thought this, however, she fulfilled the request.

Mr. Scamphers looked up at her from his desk, his moustache hiding too much of his mouth to reveal a readable facial expression.

“I just stopped by because I finished my data binder and…” She trailed off, unsure what to say. Mr. Scamphers had always seemed so dismissive.

“Great! You’re the first one.” His tone was more enthusiastic than she’d expected.

“Actually, I had most of this done a week ago, but—”

Mr. Scamphers lowered his voice. “But our principal didn’t send out the final form until this morning, right?”

Something in Maybelline’s heart clicked into alignment. “Exactly.”

Mr. Scamphers gestured toward the wall separating the two offices, his voice still low. “I was the one who reminded him. I told him, the district guidelines say all pre-test data is to be printed and organized into binders with a goal-setting cover sheet no more than thirty days into the school year. But what can I say? The main office doesn’t exactly do things the way I would.”

“Well, some of the teachers around here don’t do things the way I would.” She stepped into the office and placed the binder on his desk. She felt brave, all of a sudden. “Then again, it must be hard to make a good data binder if you barely even look at the data.”

“Interesting.” Mr. Scamphers’s thick moustache lifted on one side in what was now almost definitely a smile. “Someone in the administration should look into that.”

“Yes,” said Maybelline, “I think someone in the administration should.”

She gathered the binder in her arms and hurried back to her classroom on light feet, barely even noticing the flyers announcing the first football game of the season.

Moments like this called for proper documentation.

By the time she finished typing and left, it was later than she’d planned. She knew Allyson and Rosemary would be waiting, giving her that look they both got on their faces when she explained how busy she was at work. The farther she drove, and the more she pictured the look, the more she thought maybe this wasn’t the best day to bring up her continued concerns about Allyson’s clothes.

Allyson had stopped complaining about the outfits she was allowed to wear to school. But Maybelline also noticed, on many afternoons, a conspicuous lack of the smudges and pen marks and lunch stains that signaled a day in fifth grade. She suspected Allyson was changing into Gabriella’s clothes before the girls left for school each morning, then changing back before Maybelline arrived.

And yet the timing always seemed wrong to bring up such a messy subject, especially on a day when she’d been the first teacher in the whole school to finish setting up her data binder. Better still, Mr. Scamphers had all but promised he would check everyo

ne else’s work.

The binder sat, radiant, on the passenger seat of Maybelline’s car. It seemed almost to be smiling at her. You, it seemed to be saying, have done everything right. She didn’t move it to the back seat until she pulled up in front of Rosemary’s house, where Allyson slipped wordlessly into the car in her unwrinkled school clothes.

NATURAL SELECTION

THE LENA WHO climbed into Hernan’s Jeep on Friday evening did not look like the Lena who taught down the hall from him at Brae Hill Valley High School. Her lips were the color of shiny pomegranate seeds. Her eyelids shimmered. She smelled like an island to which Hernan would gladly have bought a one-way ticket.

But all he said was, “Nice dress.”

It wasn’t even really a dress, but rather a continuous piece of fabric that wrapped around her, staying in place due to some undiscovered law of physics. Tiny seashells hung from the bottom, clicking against one another as she settled into the passenger seat. “Thanks. You look good, too.”

Hernan wore jeans and a green polo shirt. He’d been to Club Seven once. It was tucked into one of the sketchier side streets near downtown, and if he remembered correctly, it didn’t have much of a formal dress code. Now, with Lena sparkling at his side, he wondered if he should have dressed up more.

“So,” said Lena, “I guess this is where we start talking about school and then keep talking about it for the whole night?”

“Yeah, well, that is the default setting.”

But they didn’t. Their conversation flowed as easily as the freeway’s nighttime traffic, not even pausing until Hernan pulled onto the exit ramp.

“Wait,” said Lena, as he turned down a side street to park, “you know where Club Seven is?”

“Yeah, my sister’s college friends threw this Latin-music party there.” Then, realizing this might make him sound like the type of twenty-nine-year-old who spent his time at college parties, he added, “It was a while ago. You?”

Adequate Yearly Progress

Adequate Yearly Progress